Chapter 1 explored how racial disparities, neighborhood conditions, and differences in mortality contribute to stunning gaps in life expectancies across the New Orleans metro. But how did such place-based inequalities come to exist in the first place? This chapter looks to the past, using historical data on changes in neighborhood racial composition and socioeconomic status to explore the evolution of neighborhood inequality over time. Chapter 3 concludes with a look to the future, returning to the implications of neighborhood life expectancy data for efforts to reduce racial and place-based inequality.

The emergence and persistence of place-based inequality may not be immediately apparent on maps that provide snapshots of data, like life expectancy. This chapter shows how the evolution and durability of place-based inequality relates to stalled progress on racial equity, as documented across a broader range of systems-level measures in The Data Center’s 2018 Prosperity Index and as implied by the disparities covered in the previous chapter.

A thread running throughout is that, while neighborhoods may stay the same, the people who live in neighborhoods change over time. As described below, during the latter decades of the 20th century, New Orleans suffered disinvestment as suburban parishes grew, leaving mortality rates in the city higher than in the rest of the metro. However, mortality rates in New Orleans have fallen dramatically since Hurricane Katrina and, since 2017, have actually dropped below mortality rates in suburban parishes. This reversal reflects changing mortality patterns, as well as uneven displacement and recovery since Hurricane Katrina and the levee failures.

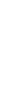

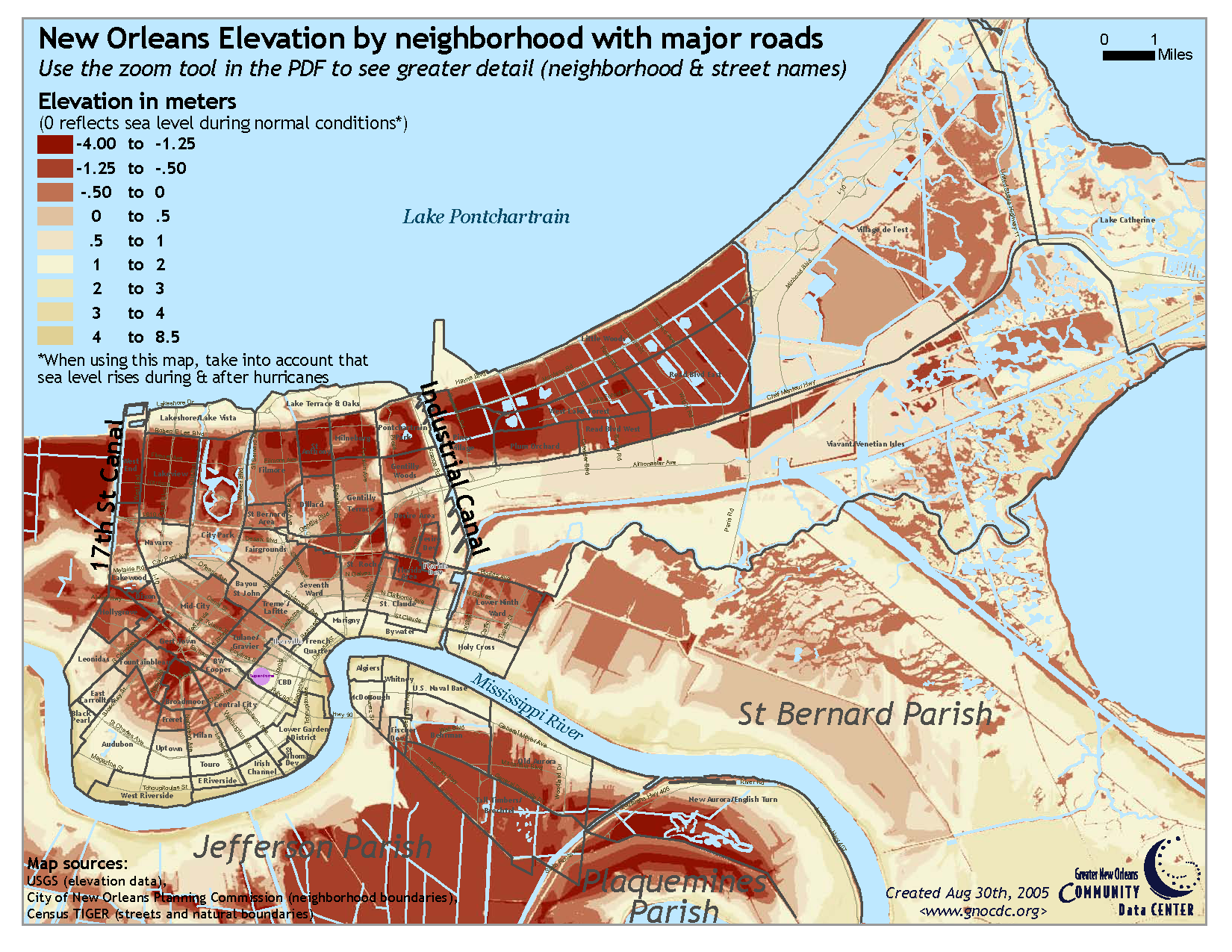

New Orleans developed in phases| Inner Ring (historic or inner core) | Middle Ring (secondary ring) | Outer Ring (suburban fringe or newest development area) |

For a more in-depth historical account of these topics, see Rigging the Real Estate Market: Segregation, Inequality, and Disaster Risk and Three Hundred Years of Human Geography in New Orleans from The New Orleans Prosperity Index: Tricentennial Collection.